Crank Up Imagery In Your Writing!

Visualization, Screenplays, and Adverb Annihilation!

I was recently in a discussion on the awesome Three Ravens Publishing Discord, and the topic of descriptive writing came up.

The questioner sought some advice for increasing their imagery in writing, and what techniques anyone employed (or resources someone may have) to do so. I thought it was worth a long-form post and I’ll get to the nitty gritty of technique in a moment, but first some context.

One of the compliments I receive regularly in terms of my writing is that the imagery I throw down in word form is very vivid, like watching a movie. A few snippets of reviews from The Caretaker illustrate this:

This boils down to my writing style, and my creative process.

There is a reason that my readers tend to see my writing as a movie in their head. It’s because the story is a movie in my head before the first word hits the page. That I “watch” the story in my mind (over the course of weeks or months, or sometimes years), is the reason I’m able to convey the imagery in movie-like quality.

My writing boils down to my ability to describe the movie I’ve watched in my head, because I think it’s cool and I want to show it to you. It’s not all that complicated, to be honest. I watch a movie, I write the movie, then you watch the movie.

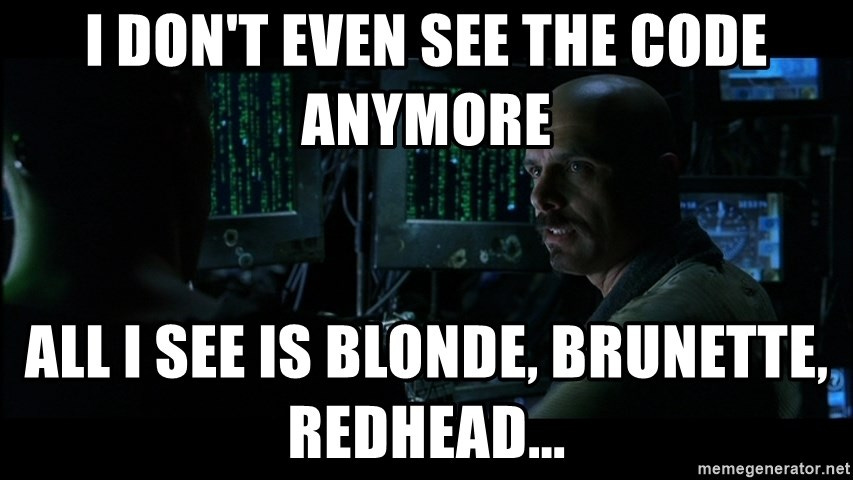

Like one of my favorite films that needs no introduction, text becomes the image because of the way it is described:

I approach writing the way a movie director would approach making a film. There’s storyboarding (all in my head), there’s wardrobe (in my head), there’s casting (again, all in my head), table readings (in my head), soundtrack, cinematography, lighting, post-production - all of it wrapped up as I obsess over characters, story, and dialogue in my brain. I watch scenes unfold over and over again, tweaking and changing them until I’m thrilled and excited to share that scene with others.

When I’m on long drives, I’m watching and re-watching the movie in my head.

When I’m laying in bed at night before going to sleep, I’m watching scenes.

When I’m making dinner, going through the routine of cooking and stirring things, I’m running through dialogue.

I am a visual person, and this is how my creative process works.

And before you ask, yes, it’s exhausting being in my brain, but this is how it works, and I accept it.

The big question is, how do you employ a technique like this in an actual, technique-y way?

You annihilate adverbs.

Now look, I’m loathe to offer writing advice on the internet. Everyone is different, everyone works differently, everyone has different creative mojo and everyone has their own style and methods of going about the shenanigans that happen between “Once Upon A Time” and “The End.”

All I’m doing here is showing you my shenanigans.

And I’m going to do it with SCREENWRITING!

So hold onto your butts, and check out this snippet of Mario Puzo’s screenplay for quite possibly the greatest movie ever put to film, The Godfather.

First, we’re going to read the scene, then we’re going to watch the scene.

Trust me, this is going to be well worth an investment of a few minutes of your time. First, the moment in text:

What do you see? I notice the phrase “mental anguish” and the word “quickly” along with “dropping the gun.”

Now, watch one of the greatest pieces of acting ever put to film, and prepare to have your mind blown.

In the screenplay, we see “mental anguish.” But we can’t say “I AM FEELING MENTAL ANGUISH” in text and expect anyone to take us seriously. Watch Pacino here. Look at his eyes in the thumbnail.

Remember, in the actual text, all we have to work with is, “mental anguish.”

First, his eyes are wide, pupils dilated. His eyes tell a story. He’s looking at Sollozzo like a true predator in this scene.

Second, you notice the slightest sheen of sweat. He’s about to murder two people in cold blood in public. You’d be sweaty, too.

Third, you have the hint in the screenplay of “voice fading into background,” which you hear when you watch the scene. It becomes muffled, Pacino is showing that his character is consumed by the thoughts of what he’s about to do. His heart must be pounding.

Then that delightful little sound in the background. Trains are rattling over rails nearby, amping up the claustrophobia of the moment. Metal screeching on rails filling his ears! It’s all too much and the only way to silence it is …

Bang.

In the continuation of the scene after he shoots, he makes for the door and drops the gun as if it’s the hottest potato he’s ever held. He quicksteps out after a pause, tosses the gun as if it’s somehow dirty, and rushes out.

And that entire scene built from “mental anguish” and “quickly.”

I’m certain Pacino didn’t need much direction to make this incredible scene. He had to read the words “mental anguish,” and think something very familiar to all of us.

“How do I show mental anguish, and not tell mental anguish?”

That’s the brilliance of an actor seeing a phrase in text, and being able to communicate it in visuals. Our job as authors trying to ramp up our descriptive writing is to do the reverse (at least, this is how I do it). Watch the scene in your head, then put it to text. Without the luxury of saying “quickly” or “nervously.” In this scene we are engaging multiple senses. Palpable tension as Pacino’s eyes dart everywhere, taking in the surroundings. The feel of sweat on his brow and the sense that his blood is rushing. The sounds of a voice being drowned out by rails screeching.

The smell of Italian food! Though that just might be me feeling hungry right now.

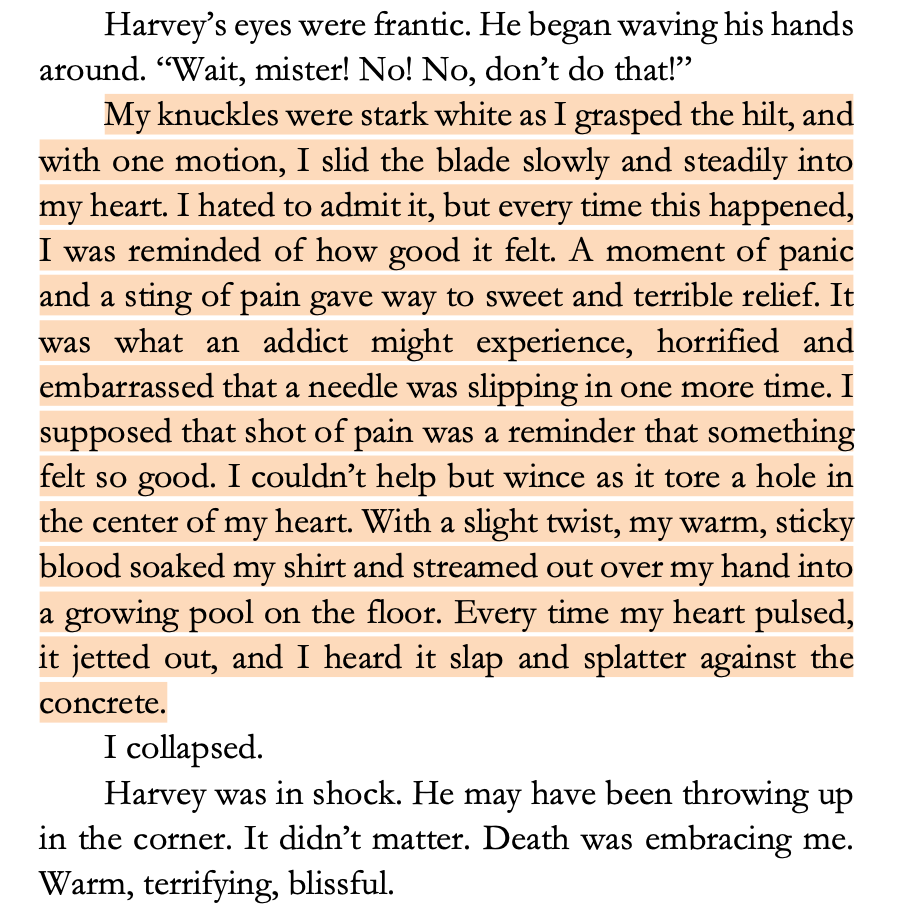

Allow me to show you a scene from “The Caretaker” that illustrates engaging the senses and writing a descriptive passage both with and without the use of adverbs.

In this particular scene, protagonist William is quite literally killing himself (long story, read the book, that’s not the point).

It starts with Harvey pleading frantically. Only it doesn’t, because I wanted more than “Harvey was pleading frantically.” I wanted frantic eyes, hand waving, and verbal begging.

While I left in “slowly and steadily” to not over-describe what is a simple hand motion of a few inches, I opted for “knuckles were stark white” instead of saying, “I nervously gripped the blade.” Instead of using words like “peacefully” or “calmly,” to illustrate the feeling of self-harm, I opted to show that by putting you in the protagonist’s head as he muses about the sweet relief of pain and death beginning to overcome life. Instead of using the word “shamefully,” I opted for describing the feeling an addict might face. The word “wince” is in place of “painfully.” All of these little choices and replacements add up to a very vivid scene.

A host of adverbs could be used in this situation, but removing them in favor of giving the actions themselves space to breathe makes the scene an impactful one early on. It’s our first introduction to William’s world, and I wanted it to be close-up and uncomfortable for the reader (which also determined the choice of first person perspective, but that’s another post).

In closing here …

The next time you’re sitting down and writing, and you spot a word like “nervously,” “hesitantly,” or “angrily,” I only suggest watching the movie in your head.

Imagine yourself in the director’s chair, speaking to your character as if they are an actor on set. You say, “Okay, you’re angrily getting out of the car and walking into your house. ACTION!”

Watch the scene unfold in your mind. Hear the door slamming. Watch the frustration as your character is so angry they trip over the dog’s tennis ball sitting in the grass because they’re seeing red and ignoring their surroundings. Feel their blood pumping and their fist clenching. Hear the hinges of the front screen door screaming as they fling it open.

All of these incredible visuals end up being the start of an unforgettable scene because you took the word “angrily,” and decided to describe the movie instead of reading the screenplay out loud.

‘til next time, happy writing!

-David